Grey | The British king Richard I imposed a law in 1197 under which it was by penalty forbidden for ´simple´ people to wear any other colour than grey. Vincent van Gogh wrote in a letter to his brother Theo in 1882: “Absolute black does not really occur. But like white, it is present in almost all other colours and forms the endless variety of greys—distinguished in tone and intensity—so that in nature one really does not see anything but tones and intensities there are only three basic colours—red, yellow, blue, ´compositesórange, green and purple. By adding black and some white one gets the endless variations of greys, red-grey, yellow-grey, blue-grey, green-grey, orange-grey, violet-grey. It is impossible to say, for instance, how many different green-greys there are, it varies endlessly. But the whole chemistry of colours is no more complicated than these few simple basics. And a good understanding of this is worth more than seventy different colours of paint, since one can make more than seventy tones and intensities with the three principal colours and white and black. He is a colourist, who, seeing a colour in nature, knows very well how to analyse it and to say, for instance, that green-grey is yellow with black and almost no blue, etc.; in short, he knows how to make the greys of nature on the palette“. What was unthinkable in earlier centuries, changed in the 15th. For the first time in the history of Western clothing, grey relegated until then to work clothes, the poor, and the habits of Franciscan monks—which were meant to be colour- less—became popular among the upper classes. Cloth makers in towns like Rouen specialized in the production of high-quality grey cloth, so great was the demand from princes and nobles. Grey became the colour of hope, joy and life. Dyers developed new grey tones which were obtained by the use of a mordant with the baths of birch and alder, adding iron sulfates and sometimes a little oak apple.

1780 | “Men and women, children and old people spin, weave and elaborate cotton and wool in the workshops. The laws promise hours and wages, but the Indians thrown into these great slave quarters or prisons only leave them when their burial hour arrives.” The original idea had been for the workshops to be sustained by Christian charity and to serve as centres for evangelism. In fact, the workshops in Peru were not only ‘abominable’ but the Indians there—locked in the workshops—‘were destined for a quick civil death.’ A main aim of the uprising led by Tupac Amaru II and Micaela Bastidas, his wife, against the Spanish authorities of Peru, was to free them by burning down these ‘prison workshops’. However, despite Micaela’s urgings, who was left in charge of their forces near Cusco, he refused to attack and take that strategic city that had been the Inca capital. This was either on the grounds that he could not kill other Indians, specifically those who were defending the Spanish-held city, or because he was sidetracked elsewhere and did not understand the realities of troop morale. This has disastrous consequences and Tupac himself was captured after being betrayed by one of his own captains, Francisco Santa Cruz. His torture was supervised by the Spanish king’s representative José Antonio de Areche: Micaela and their son Hipolito have their tongues cut out before being garrotted. Tupac’s own body is tied to four horsemen riding in different direc- tions, but his body does not split, and a violent rainstorm begins.

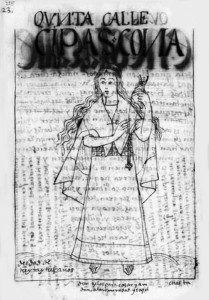

Taking full advantage of this gruesome defeat of Tupac Amaru II and his sup- porters, Areche delivers a proclamation against Inca dress. A Spanish prohibi- tion had been made as early as 1575, but was now repeated with force. “Indians are forbidden to wear the dress of the gentry, and especially of the nobility, which serves only to remind them of what the ancient Incas wore, bringing back memo- ries that merely cause them to feel more and more hatred for the ruling nation; apart from looking ridiculous and hardly in keeping with the purity of our religion, since it features in various places the sun which was their first deity; this order extends to all provinces of this Southern Americas, totally abolishing such cloth- ing…and at the same time all paintings or portraits of the Incas…And to that end that these Indians should rid themselves of the hatred they have conceived against Spaniards, that they should dress in clothing prescribed by law.”

Threads speak. They entwine themselves into our hearts and dreams. Threads speak of many things. They talk about the present, about exotic tourism and about our own fixation with “other worlds”; they suggest hidden dialogues, interior to Andean histories and worlds—that speak to us only obliquely. They also talk of intimacy, of the human relations embodied in producing extraordinary art/textiles; they talk of enduring burdens of exploitation; they talk about the special joys and travails of women—who, after all, are the weaving artists of the Andes.

Weaving is women’s work and women’s pleasure; women’s modes of expression and creativity; women’s history-writing of community and family. It is a knowledge, art, grace, geometry that has been transmitted over centuries from generations of women to generations of women: how to card wool, how to spin wool, how to dye wool, how to set up a loom, how to transform thread into meaningful fabric. Centuries-old Andean graves hold women buried with their spindle whorls.

Textiles are culture-work in the Andes. Textiles are chronicles and history lessons; textiles bind kin and comadres; textiles are symbols of wealth and power; textiles are the source of wealth and power. Textiles, like this one, communicate with worlds beyond. Textiles represent a social vision of community—in time and space. They also personify the social ties of “ayni” (reciprocity)—between people and between people and the divine—that ultimately ground anything produced by Andeans.

Textiles, and the women that produced them, could be translated into wealth by imperial forces that shaped Andean experience. Before Europe colonized the Americas, native Andean emperors demanded weavings made by women of the peasantry and by the elite women called the Inca’s “chosen” or “aclla”. Indigenous monarchs, however, recognized obligations to those under their rule and honored the integrity of women’s work. Women, the producers of Andean textiles, including tribute, remained embodied in production.

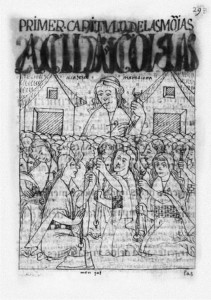

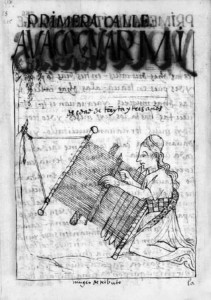

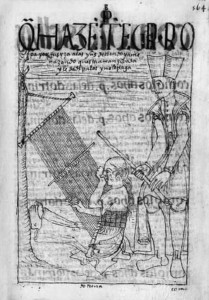

Guaman Poma de Ayala’s 1,000 pages letter of protest to the Crown, acknowledges the importance of textiles in Andean life. Look at his drawings of the “uncus” (ponchos) worn by Inca kings, symbols of Inca dominion and the history of Inca dynasties (1). Look at the drawings of Inca queens dressed in shawls filled with meanings of their status and authority (1); or of the “aclla”, or chosen women, carrying the tools that brought these shawls and uncus into existence (2); or the Inca census, with iconic women, representing “stages of life”, who are tied to weaving, with spindles and thread (3—5). Weaving substantiated women’s powers, as Andeans knew well.

“The priests want money, money and more money, so they force women to serve them as spinners [and] weavers…” says Guaman Poma. Spanish colonists brought very different understandings of textiles and institutions of textile production to the Andes. Women were forced to work in proto- factories, alienated from what they made and the creative means to produce their lives. Markets, money and “commodities” insinuated themselves into Andean life. Spanish economic practices distorted the tie between weaver and textile, transforming textiles and the women’s labor that produced them into commodities. See Guaman Poma’s devastating portrayal of how priests shamelessly beat women so they could have “money, money, and more money” in their coffers (6).

But neither colonialism nor modern capitalism can obliterate a textile’s soul. We don’t know who created this extraordinary textile on display. Yes, this textile has become a commodity, passing from the woman who created it to others. Eventually this ritual cloth found its way to an exceptional Lima shop selling Andean artisanry; and, then, it crossed channels and oceans, and found its way to my door and to this exhibition. I hope and believe that in spite of the journeys traversed by this textile, the woman who spun the wool, died the yarn, set up the loom, and transformed her vision into a textile of beauty, is still, in Andean spirit, embedded in its threads, is still, in Andean spirit, laying claim to what she produced, is still, in Andean spirit, speaking to us.