Wax Print | A great variety of brilliantly coloured and designed cloths have been, and are, produced in all areas of Africa, but some of the most popular and celebrated are wax-printed cottons, which are an import. West Africa had been involved in the global textile trade world since the 16th century and this involved both the importing and exporting of cloth. The story of wax-print is one of a globalized world transacted by colonialism, which begins in Indonesia where there was a long tradition of handmade batiks using wax as the dye resist. Dutch colonisers were impressed and starting in the 1850s the Dutch firm Vlisco copied the technique and produced their own version using engraved roller print machines, and resin on either side of the cloth rather than wax. They then began to export it back to Indonesia and in the 1870s they also found a market in West Africa. There are different versions of how this happened. One is that Dutch freighters, on their way to Indonesia with such a cargo, stopped at various African ports and developed a client base there. It may also be that they sold them on the way back because they were seen as inferior to the domestic product in Indonesia. So much so, that by 1900 competition in the Asian colony was so fierce that the market was in effect lost. Within this time-frame there was a yet more entangled story of colonialisms. After the Java War of 1825—30, the Dutch experienced a chronic shortage of military manpower in Indonesia, and began a programme of recruiting in West Africa. Its Department of Colonies remembered that there were Dutch possessions on the Guinea coast where commercial activity had fallen away following the official abolition of the slave trade. In 1837 the Dutch king signed a deal with the king of the Ashanti whereby recruits would be supplied. If they had begun as slaves the guarantee was that recruitment would make them into free men. One thought had been that the Africans would be less vulnerable to disease in the Asian colony, which accounted for more military deaths than actual fighting. This was not the case, many West Africans died. Some however did return to what is now Ghana and may well have brought the cloths with them.

The Dutch may also have had a head start in Africa because their colonial history was nothing like as bad as the grim British story, but by 1909 the Manchester firm ABC were also in the wax-print cloth business along side Vlisco. The cloth has remained a status item till today with labels to match. Apart from that of Holland there are Real English Wax; Veritable Java Print; Guaranteed Dutch Java; and Veritable Dutch Hollandaise. These prestigious labels ironically have ‘mistakes’ in the cloth, but these it turns out, are part of the attraction; during the ‘wax’ printing the resin is liable to crack giving the textile its ‘cracked’ look admired in the West African aesthetic. The manufacturers have also become pragmatic. “Earlier design motifs used plants and animals believed to be univer- sal to all cultures. From the middle of the 20th century, however, more effort has been made in creating authentic design by using Indigenous African textiles to create similar motifs.” Pragmatic enough also to impose very tight security on their design departments; put a grip on their intellectual property rights by use of patent; and for both companies to have opened manufacturing subsidiaries in Ghana.In a twist common to contemporary globalisation these companies are now being challenged by Chinese producers. The British ABC and its ATL Ghana- ian subsidiary have in fact been bought by a Chinese company initially attracted to the business by African traders going to China to reproduce wax-print cloth cheaper. Rather like the 19th century Dutch, the first Chinese cloths were low quality but this is said to be “changing rapidly,” and they too are claiming patents on designs originating in Africa, which is creating unemployment in Ghana itself.

1819 | “The history of the weavers in the 19th century is haunted by the legend of better days.” The best days for the independent weaver had gone by 1819, but in August they came together with factory-based spinners for the first time, some 60 to 100,000 of them with their children, to Peterloo Fields in Manchester, to demonstrate for the political rights which they believed was needed to improve their much worsened living conditions, and necessary to their dignity. Power looms did exist, but in small number, and were not the reason for the hardship of hand-loom weavers at a time when so much yarn was being produced to be woven. Rather, it resulted from a capitalist strategy—aided by the British state when it removed craft status—of driving down the price paid to weavers during recessions, and keeping it low when demand for cloth returned. It was deliberate and full of unambiguous class hatred for weavers who had at least the freedom to start work as and when they wanted. This hatred is clear in the voice of a magistrate in 1818. For him, some years before the weavers had been extravagantly paid and could maintain themselves in a state of luxury by working only 3 or 4 days. In a state of luxury is an exaggeration to say the least, but the cloth merchants, mill-owners and the rest were determined that weavers would never have anything like it again. They had already shown this with a series of executions of men accused of being machine-breaking Luddites between 1812 and 1817, and in the shooting of workers by armed guards employed by mill-owners and by what was, in effect, a military occupation of Yorkshire and Lancashire.

To the 1819 demonstration came the Lees and Saddleworth Weavers Union with a pitch-black flag, lettered in white paint with LOVE, two hands joined and a heart. It was this and the very discipline of the crowd which so panicked the gentry who liked to consider them as a rabble. “The peaceable demeanour of so many thousand Unemployed Men is not natural,” commented one General Byng. This very peacefulness and the nature of the flag were interpreted as threatening. Thereupon they were attacked by both the regular Hussars of the British army and the Manchester Yeomanry, the armed bourgeoisie, both on horseback and armed with sabres. Eleven were killed and over 400 injured, mostly with sabre wounds. More than a hundred of the injured were women or girls. There is no evidence that the British state organized the attack, but they were not slow to congratulate those who had done it. Despite this attack and the repressive laws that followed, weavers were very significant in the national Chartist movement that followed in the 1830s when their material conditions were worse still.

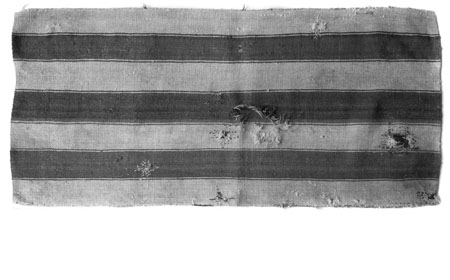

In May 2011, Ines brought this bag to Berlin so we could write about it. When we asked about its origins and the circumstances surrounding the purchase, she said she first saw this kind of bag in a textile museum in Cusco and later bought this particular one from a textile dealer because it had more patches than the others. It is made of alpaca wool and she estimates that it’s about one hundred years old. These bags were made in various sizes, depending whether they were to be carried by a donkey or a mule and depending what kind of crops were meant to be transported in them. People stopped making these bags about forty years ago. They used to be woven by the women in the family, but because the men have gone to the cities to work, the women have to cultivate the fields by themselves and have no time to weave bags.

A number of factors have contributed to the more than sixty-year duration of the flight from the land in Peru: the unequal distribution of property ownership, the failure of agrarian reform, the civil war, poor harvests and the impossibility to sell crops, and unemployment, including in the cities. In 2006, 72.2% of Peru’s population lived in the cities and 27.8% in the country. The areas with the high- est migration rates have been the same for fifty years: Huancavelica, Ayacucho, and Cusco. The flight from the land continued with waves of migration to Spain, Italy, Japan, and especially the USA. In 2007, it was estimated that three million Peruvians migrate each year. Most of them are young women who get jobs taking care of the elderly or working in the households of people who may very well happen to work in the offices of the same banks, chemical companies, seed corporations, and government departments whose decisions are partly responsible for the land flight in Peru. The young women are often illegal and have no rights. In fact, that’s what distinguishes them from office workers. It’s like the difference between seed corporations and farmers.

Ines thinks this bag was carried by a donkey and was used to transport corn. If it were used for hay, fabric, or larger fruits it would not have been necessary to mend the many holes so carefully. Andreas thinks that if you lay the bag flat, it tells a tale of parceled fields or freshly turned potato beds, of the sky above, and of the clouds, which are bigger there than anywhere. It could be that the bag had a signaling effect. Maybe the stripes were like a code that said exactly what was in the bag. He’s thinking of the economic circuit in which these bags were involved: from the country to the city, to the mines, quarries, or factories. There’s nothing romantic about it; the mended holes show how precious each grain of corn was, how hard to come by.

Alice remembers a story from the Ingeniero White district in the town of Bahia Blanca on the Atlantic coast of Argentina. Ingeniero White is a big port for shipping grain to Europe. Along the roads, the locals sweep up the grains that fall from the trucks and feed their chickens with it. When money wasn’t worth anything in the crisis of 2001, the chickens became currency.

* Cf. Aída García Naranjo Morales: “The Peruvian Migration Phenomenon”, Centro de Asesoría Laboral del Perú, September, 2007.